The Artsakhians call their dialect ‘մեր լյուզուն’, meaning ‘our language’. They refer to the Armenian spoken in Yerevan as just ‘Armenian’.

At home, in everyday life, people mostly speak mer luzoon, and only revert to the official Armenian language in formal situations.

The Artsakh dialect also prevails at schools, healthcare institutions and even in theatres. It has become the language of art and itself a work of art.

And the Artsakhians do not mind, because they believe that ‘մեր լյուզուն լուխճանաց քաղծըրնա, հտէ տի’: ‘our language is the sweetest of all, just like that’.

Literary Armenian: from one school bell to another

5-year old Arno Badalyan speaks to his peers in the dialect of his native Maghavouz village, but once he gets home, he switches to fluent literary Armenian. He has been doing it for years. Sometimes, of course, he speaks yet a third language: a mix of the village dialect and the literary Armenian he was taught by his mom.

The boy’s mother, Gohar Avanesyan, is a history teacher at Maghavouz’s school. She says that the idea of teaching her son to speak literary Armenian at home just hit her at some point.

“Arno was barely two years old when I started reading fairy tales to him. Since he couldn’t understand most of the literary words, I had to retell him the entire fairy tale in the dialect.”

That was when Gohar decided she would speak to her son exclusively in literally Armenian. “I knew he would still learn the dialect from his peers.”

According to her, most of her pupils can only speak their local dialect when they start primary school. The picture only changes in secondary and high school.

“I teach history to pupils aged from 10 to 17, and I can assure you that they fully understand the material in literary Armenian. In the classroom, I sometimes use idioms from the dialect to give some typical description or to put the pupils at ease,” she says.

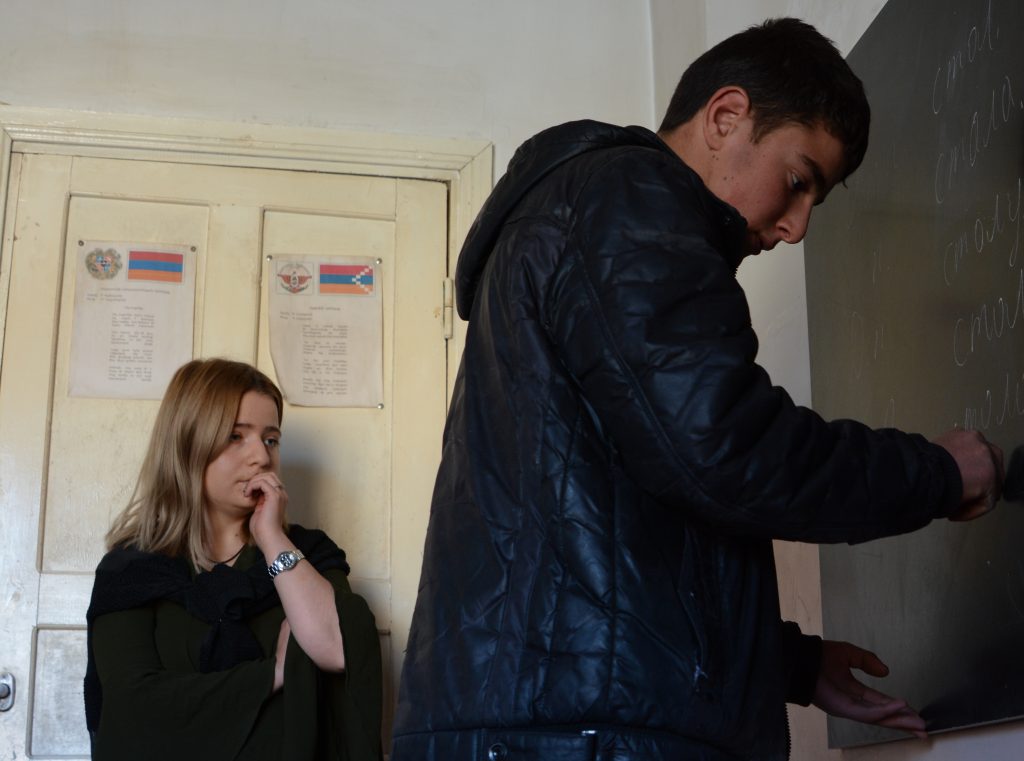

A school in Martuni, a town situated 40 km south of Artsakh’s capital city of Stepanakert, bears the name of Nelson Stepanyan, a WW2 Soviet pilot of Armenian descent. Starting in the early 1990s and until the mid-2000s, the school used literary Armenian and the Martuni dialect equally in the teaching process. Today most of the curriculum is taught in literary Armenian. There are many reasons why it’s happening.

The children of two military officers who moved to Martuni from Armenia are in Elza Khachatryan’s class. She says that she requires her students to speak in literary Armenian even during breaks, so that the two students from Armenia understand everything. According to Elsa Khachatryan, it is crucial that children learn to communicate in literary Armenian while still at elementary school.

Tinatin Grigoryan has been a teacher for over 25 years. She now teaches geography at the Nelson Stepanyan school in Martuni. She says that she teaches entirely in literary Armenian and only makes additional comments in the dialect. However, some of the pupils answer her questions in the literary language, and some use the dialect. Grigoryan says that as soon as the pupils get tired during the lesson, a few words in the dialect serve to wake them up.

Until 2004, the school had a Russian department, where the entire curriculum was in Russian, taught by teachers who got their degrees in Russian. Once the Russian department closed down, those teachers stayed at the school and moved to the Armenian department, trying to teach their classes in literary Armenian. However, some of them are not fully fluent in literary Armenian, so the dialect remains the main language of communication.

Mer Luzoon vs ‘Armenian’

Vladimir Doloukhoanian teaches history at the school for children from the New Seysoulan and Hovtashen communities of the Martakert region, which lies north of Stepanakert. The residents of these communities are new settlers who moved here during the last two decades from various places, chiefly from Armenia. Doloukhoanian believes that use of the dialect during classes complements the literary Armenian rather than replacing it.

“There are cases when the teacher speaks in the dialect, which is more commonly used in everyday life. This allows us to use various aphorisms, synonyms, names of various objects or phenomena in order to make the message more understandable for the students. In this case, the dialect, in fact, comes to compliment and not replace literary speech, the presentation of material in the literary language,” says Doloukhoanian.

Compared to communities that have long histories and their own dialects, schooling in literary Armenian is easier to organize in resettled communities since most of the children speak the Yerevan vernacular, which is similar to literary Armenian.

Still, just like in other parts of Artsakh, the colloquial speech in New Seysoulan and Hovtashen is a Babylonian mix of words and expressions from literary Armenian, the Artsakh dialect and Russian. While the main language of communication at the school is the Yerevan dialect, it isn’t always possible to teach exclusively in literary Armenian.

The Vaghazin village, situated 100 km west of the capital Stepanakert, was populated by Kurds prior to the Karabakh conflict. At the beginning of the 2000s, it was resettled by families from Armenia.

Today, there are just 10 students at the village secondary school, and as many teachers.

Narine Vardanyan, the teacher of Armenian language and literature, admits that she occasionally switches to her native Shamshadin dialect when

“Because of the shortage of teachers, some of the students are having trouble understanding classical literature. Sometimes I have to explain the meaning of particular words using the dialect,” says Ms. Vardanyan.

More than 1100 students aged 12-18, of whom about 400 come from various regions of Artsakh, attend the Tumo Center for Creative Technologies in Stepanakert.

In the capital of Artsakh, the main language of learning and communication is the local dialect. At Tumo, students and coaches speak each in their own language. Most students use the dialect when talking to coaches who come from Yerevan or the Armenian Diaspora, which, of course, complicates communication.

Asked whether they can speak literary Armenian, one of the students replies in literary Armenian, “Of course I can,” and adds, automatically switching to the native dialect, “But I am more used to speaking mer luzoon.”

Coaches coming from Yerevan often have to learn the Artsakh dialect in order to understand ‘the language of the students.’

“You won’t believe it, but we have students from villages who are having trouble reading Armenian. Schooling here is exclusively in Armenian and all answers must be written down using the Armenian alphabet and syntax,” says Anna Harutyunyan, a coach at Tumo Stepanakert.

To be continued…

By Syuzanna Avanesyan, Narine Aghalyan, Knar Babayan, Sarine Hayriryan, Alyona Melqumyan, Mariam Sargsyan, Marut Vanyan