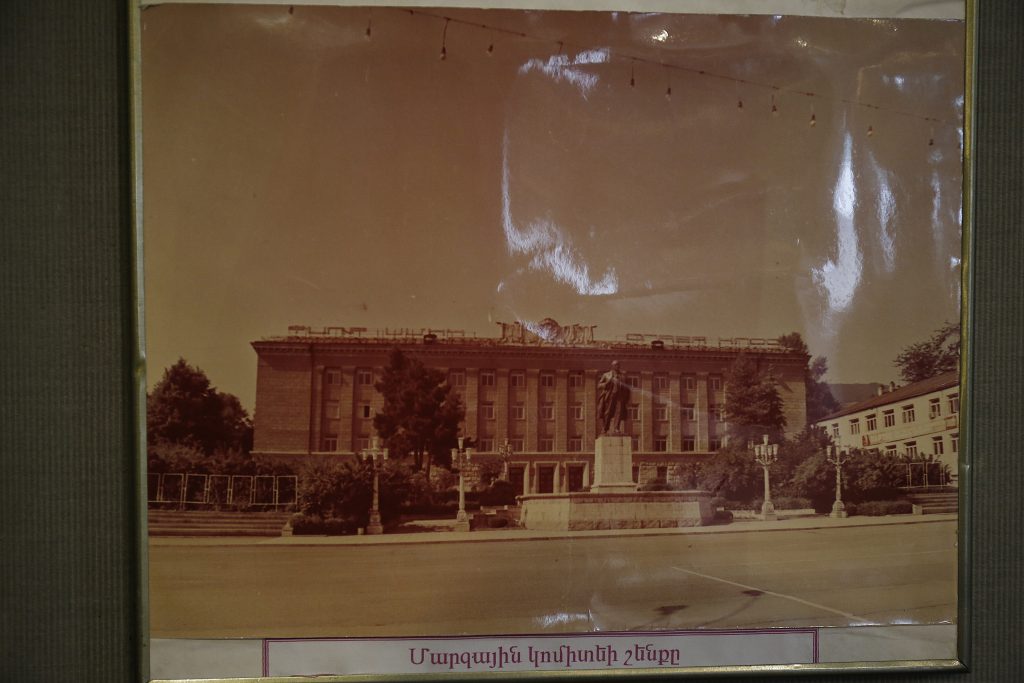

In old photos from before 1988, you can see the inhabitants of Stepanakert take evening walks in the central square under the feet of the towering statue of Lenin. Lenin is gone and so is the Soviet ideology that made Karabakh part of Soviet Azerbaijan in the 1920s. That ideology preached the brotherhood of nations but in fact often pushed nations against each other.

Today, when people walk around the square, no one thinks that in the recent past there was a huge statue of Lenin here.

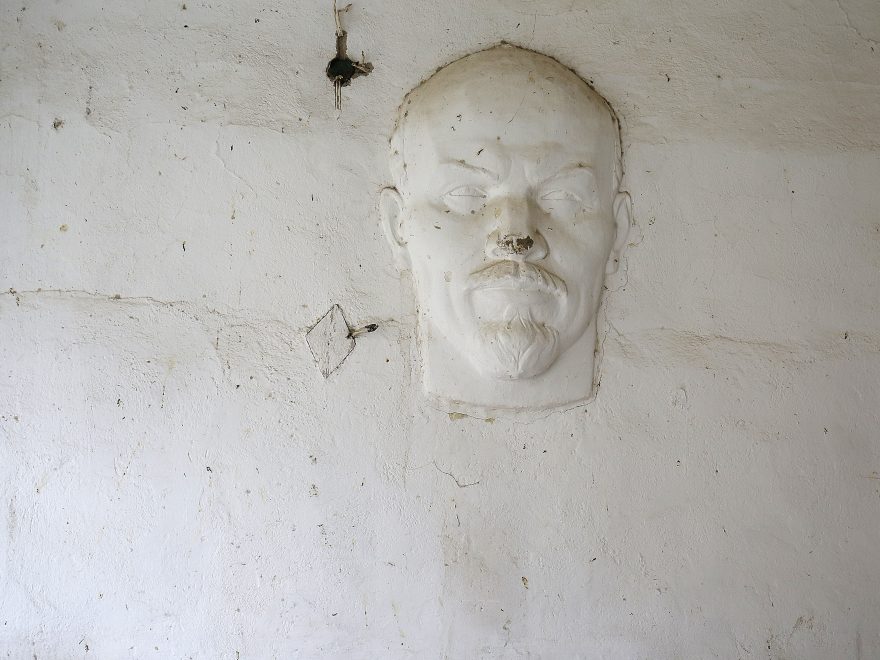

Lenin greets us every morning

For 20 years, 60-year-old Sveta Avagyan has started her day with cleaning the building of the Togհ municipality. She works here as a cleaner and after finishing her daily duty she takes a long broom, stands on her tiptoes and stretches up to reach the top of the wall sculpture.

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, the eternal living leader of the Communist Party, greets the guests of the municipality from the left wall of the corridor with his stern look and broken nose. The plaster sculpture of the Soviet leader was installed in the 1950-60s and was not removed during or after the first Karabakh war. Until today, it is almost intact and seems to have long been forgotten.

“If we thought that Karabakh’s fate would somehow change with the removal of Lenin’s sculpture, we would do it today. But you know, he a just a guy who greets us every morning here,” says Vahid Sahakyan, 57, the secretary of the community administration.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, several rooms in the municipality were partially renovated. Sahakyan says, “Maybe when it comes to repairing the corridor, they will remove the monument, but as of today it does not bother anyone. Only nesting birds dare into the corridor to soil the leader’s head.

Sveta Avagyan remembers well that in Togh, as in all the villages and towns across the country, there was no shortage of statues of Soviet leaders.

“In the village there was a huge statue of Lenin holding out his hand. We played hopscotch there every day. And a portrait of Stalin took pride of place at the school,” Sveta recalls.

While the people of Togh have got used to the sculpture in the municipality or just forgotten about it, at the school a bust of Lenin was simply thrown into the nearest dump. It would probably have stayed there if one day, they had not decided to plant a vineyard on that spot. The statue was moved to the yard of the school, causing controversy among the villagers. Employees of the Togh School of Art expressed their protest by painting the leader in the colours of the German flag.

The director of the art school, Suzanna Balayan, says that they tried to paint the bust in the most unpleasant colours (red, yellow, black).

“Someone who betrayed our nation so cruelly does not deserve any other treatment,” says Balayan.

By betrayal, Balayan meant that Lenin, in order to expand the world revolution, provided Ataturk with weapons and gold that he then used against the Armenians. “And in 1920-1921, agreements between Russia and Turkey were concluded at the expense of Armenia, Western Armenia, Karabakh and Nakhichevan,” she adds.

Lenin is a theatrical requisite

In different parts of the temporarily closed building of Stepanakert’s Vahram Papazyan State Drama Theatre, you can find everything, from old posters to a huge plaster bust of Lenin.

The communist leader’s head is covered in dust. With a broken nose, the bust is rotting in the basement, under the rotating scene that no longer works. There was a time when at all communist party events, this same bust occupied its place of honour at the front of the stage.

The security guard of the theatre leads us to the basement. He tells us to turn on the flashlights in our phones and watch our step. The previous time someone went down here when kids from Stepanakert’s Tumo were shooting a documentary about the theatre building.

“In recent years, only you and the filmmakers wanted to see the bust,” the security guard says honestly.

66-year-old Karine Alaverdyan, head of the theatre’s department of literature and art, says that after its founding in 1952, all important Soviet events were held at the theatre: communist party meetings, planning, various government events, anniversary parties.

“All these events took place under the stern wise gaze of Vladimir Ilyich. We would set up a special red corner on the stage and place the bust of the leader there,” recalls Karine Alaverdyan, adding that today the bust is stored as a prop.

Alaverdyan regrets that Armenians do not have a culture of preserving and respecting history.

“Be it good or bad, we had a 70-year Soviet biography. Those 70 years have been part of our common history, and I think that history should not be neglected like this,” says Alaverdyan. She believes all the statues and sculptures of the Soviet period must be collected and placed in some alley in the city.

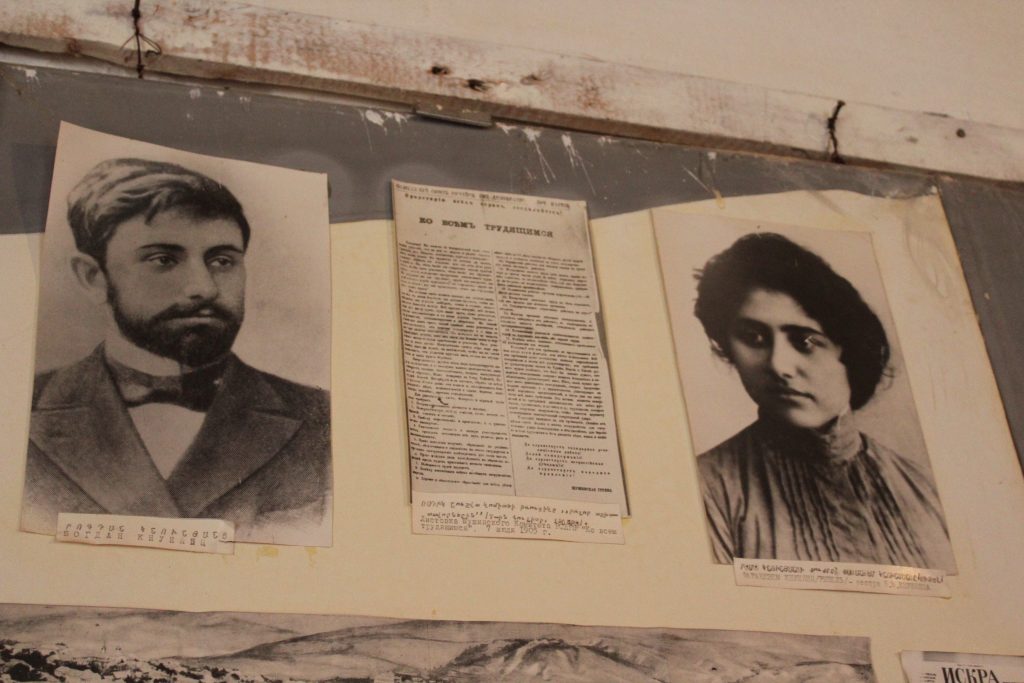

Bogdan Knunyants. The famous Soviet figure and the small village of Karabakh

“Oops, is that even possible?” This is how inhabitants of the Nngi village of Martuni region reacted a year ago, when they heard about the beheading of the statue of a prominent Bolshevik figure, professional revolutionary Bogdan Knunyants.

For almost a year, the statue was headless, with the head carefully wrapped in a plastic sheet and set at his feet.

The village of Nngi with a population of about 300 is located 18 km from the capital Stepanakert. In the 1950s, residents of Nngi built a monument to honour their fellow villager Knunyants.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the villagers could not tolerate a headless statue of Bolshevik Knunyants. Getting the job done has become a matter of honour for them. Philanthropists from Krasnodar, a city in Russia, and from Yerevan came up with 3 million drams to install a new bust of Bogdan Knunyants, and to improve the territory around the sculpture.

The old statue was dismantled and taken away in an unknown direction.

Seven Knunyants brothers once moved from Dagestan to Nngi, establishing the dynasty of Nrkrarants. We cannot say what that name means.

Bogdan’s father, Mirzajan, was the richest of the brothers. He bought land and watermills for his brothers in the village, but he himself moved to Shushi with his family, where his son Bogdan received his primary education at Real College in 1886-1895. Then Bogdan graduated from the Department of Chemistry of the Petersburg Technological Institute, and in 1897, joined the Communist Party. A professional revolutionary, Bogdan Knunyants was among the leaders of the Leninist section in the Baku bureau of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party.

At some point returned to Karabakh to avoid persecution and started to participate in the publication of the Iskra newspaper.

Today, only one descendant of the Nrkraranc dynasty lives in Nngi. Poghos remembers nothing about his relative Bogdan Knunyants except that “he was a good man”, «նա լավ մարդ ա իլալ».

In the basement of the Nngi School, there is a small museum of local where one can find no portraits of heroes of the last war or even the Artsakh flag. The Nngi History Museum is completely dedicated to Bogdan Knunyants. His life journey is exhibited there through maps, photographs, speeches and other materials.

At the edge the Stepanakert-Nngi-Martuni highway, at a vantage point, there is a memorial to soldiers killed in the Artsakh war, which, according to the mayor of the village, requires renovation to the tune of some 300,000 drams. However, the villagers and the heads of state pass by this monument quickly, leaving it unnoticed.

Stalin’s portrait as a symbol of love and loyalty

For 63 years now, the image of the father of the Soviet peoples, Joseph Stalin, has occupied an honourable place in the house of Alik Ayriyan from the village of Dahrav in Artsakh. Stalin has long been a member of the family. If the elders have put up with his presence long ago, Alik’s 27 great-grandchildren who have never seen the Soviet Union, are wondering, “Why did you hang the picture of Stalin on the wall?”

In 1956, when, following the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, orders to dismantle the personality cult of Stalin reached the autonomous region of Nagorno-Karabakh, Alik Ayriyanan, then an employee at the village council, refused to put the image of Stalin away in the basement. A soldier who fought in WW2, Alik was unflinching. “I fought the war in his name and I will not allow his portrait to be desecrated.”

Stalin, enclosed in a thick wooden frame, was a companion of the ups and downs of Alik and his wife, Asya, a guest at their four children’s weddings, a witness of the upbringing of their 13 grandchildren. And now the proud Supreme Commander proudly watches the Hayriyan’s 27 great-grandchildren grow up.

After her husband’s death, 93-year-old Asya Hayriyan takes special care cleaning Stalin’s picture, which has escaped the Khrushchev Thaw.

“As long as I am alive, it will not be removed”, – Asya Hayriyan firmly decided.

The Hayriyans admit that Stalin’s picture in their house is not a sign of personal worship, but a symbol of love and devotion towards their great-grandfather and great-grandmother.

People in Khnapat village do not know what to do with the Lenin statue

Izabella Hayrapetyan, known as Ziba, lives in the village of Khnapat. There is a church behind her house and a statue of Soviet leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin standing in her yard, with a book in his right hand.

We asked why they didn’t remove the statue long ago. The answer was at the same time strange and unequivocal, “Who needs it?”

In the 1990s, they wanted to remove the statue of Lenin and transfer it to the Askeran Museum. A special commission was convened for this matter. They came to the village, looked at the statue and said, “We would take it if his hand were outstretched.” This is how Lenin remained in Khnapat.

A statue of Stalin used to stand a few meters away. However, the statue was removed back in the Soviet times.

“Gevorgyan from the Komsomol was leading the operation. At night, Stalin was dismantled, and pieces of the statue were hidden in a neighbouring house,” says 103-year-old Ashkhen Baghdasaryan, a resident of Khnapat.

Ziba is already used to seeing grandfather Lenin’s statue in her yard. But she would not mind if the statue were removed. However, it is surrounded by houses on all three sides, and on the fourth side, there is a small pomegranate garden.

“They need a truck to move the statue. But the street is so narrow that no car can enter.”

The statue of the great leader remains in the centre of the village of Khnapat.

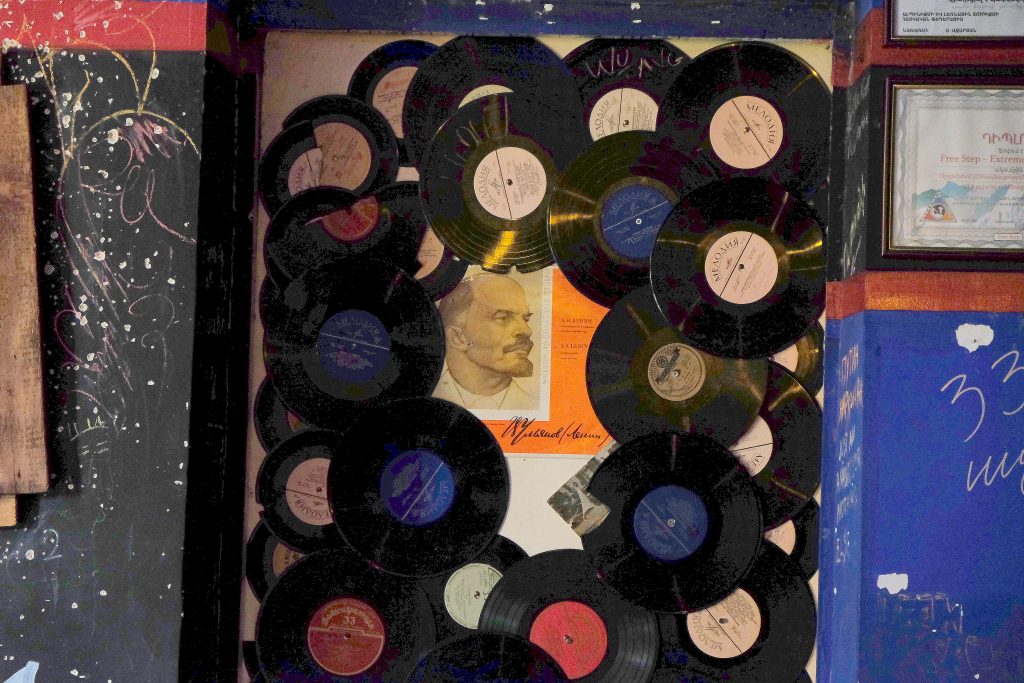

Statues, posters and slogans from the Soviet times can still be found in various villages of Artsakh. But Stepanakert’s only pub, called Bardak, meaning “disorder,” has turned Soviet symbols into interior speciality.

Here you can see various Soviet-made items, posters and portraits of Lenin. There is one on the front door and another on the toilet door.

“When I opened the pub back in 2017, there were only a few chairs. To fill that emptiness, I started to bring old Soviet artefacts from home and furnish the pub. Then it turned into something like a hobby. Even today, my friends bring me old Soviet stuff dear to them. They don’t have enough space at home to keep it but they don’t want to throw it away. I look well after the objects, I often fix the items that are broken or are not working,” says the owner of the pub, 28-year-old Azat Adamyan.

Azat was not raised during the USSR. He grew up after its collapse, but keeps the symbols.

“All these items are the history of the years lived by my parents. Nowadays, adults sometimes bring their children to the pub as if it were a museum, to show them objects that have no use in our days,” remembers Adamyan, adding that one of the children studied the telephone for a while and exclaimed, “I have never seen a telephone that looks like a shower”.

And if…

If things remain how they are, the statues and busts of Lenin, as well as the portraits of Stalin will remain in the streets and apartments of Artsakh for a long time. However, times have changed and the communist values are no longer of the same importance in Artsakh. New values have emerged; the new generation has a different viewpoint and perception of the ideology of the past and the present.

What if we gather all those statues and put them in one place, let’s say, in a park that would become a unique museum of Soviet idols?

Authors:

Susanna Avanesyan

Knar Babayan

Lusine Tevosyan

Sarine Hayriyan

Alyona Melkumyan