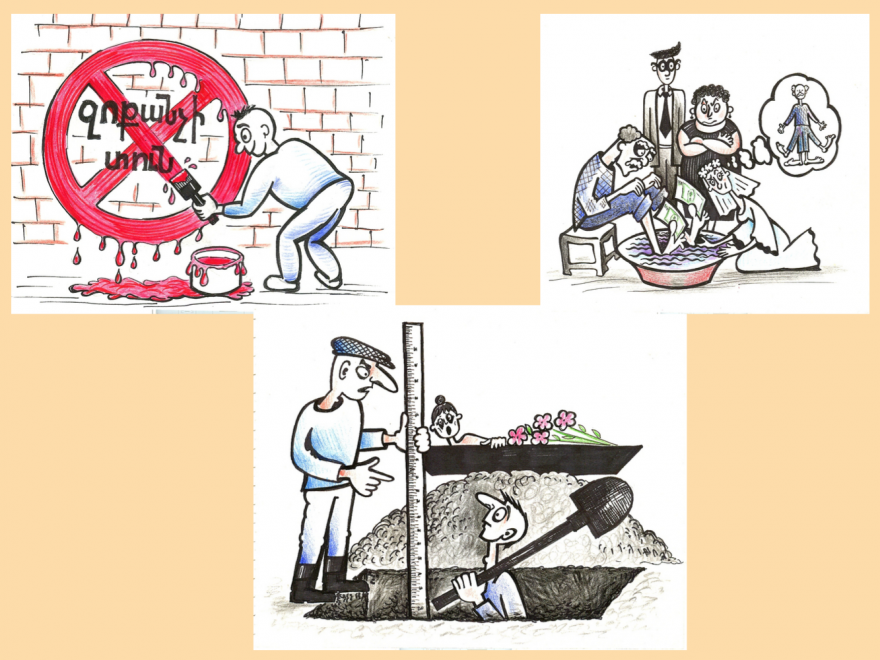

The women and men of Artsakh live in different worlds. The man’s world is mostly outdoors, the woman’s world is indoors. The duties of women are to wash, clean, cook, and raise children, whereas the men must be breadwinners.

The woman must fulfil her duties even if the man does not do his part. In Artsakh, one of the duties of a daughter-in-law is to wash her father-in-law’s feet.

In public, women are expected to be meek, humble and obedient. Many women do not even call their husbands by name. As a result, women appear subordinate to men. And men are losing their sense of responsibility.

When they die, women in Artsakh are buried half a meter deeper than men.

“Another pair of feet…”

Zina Khachatryan, 85, from the village of Khatsi in the Martuni province, was only 13 when she got married. Zina says that her grandmother taught her the duties of a wife from an early age. When moving into her husband’s house, she was well aware of her expected responsibilities as a wife.

“In the evening, my mother-in-law used to say: bring some hot water, and go and wash the feet of your father-in-law,” says Zina Khachatryan.

When asked if it were possible to skip that particular duty, Zina exclaimed in surprise:

“What are you saying? Unlike nowadays, in our times, a daughter-in-law would respect and love her father-in-law like her own father.” Zina continued to describe the ceremony of washing feet in detail.

“I remember the first time I washed the feet of my father-in-law, scrupled and ashamed, first I washed his left foot, then the right one, and afterwards dried them gently with a towel. To say that I was disgusted would be a lie. My father-in-law was a good man, and my husband was watching me, so the future of our relationship depended on the outcome of this ceremony,” Zina recalls.

There are many legends associated with the tradition of washing a father-in-law’s feet. Most of them are seasoned with humour.

It is said that in one of the villages of Artsakh during the feet washing ceremony, the father-in-law gave the bride 25 roubles for each foot. And the bride, unperturbed, replied, “Dad, I wish you had another pair of feet”.

In addition to the duties of the daughter-in-law, there was also a rule regarding visiting her parents. She wasn’t allowed to visit her parents very often, just once a month for a few hours.

“A girl who lives by the rules of her husband’s home becomes the “light” of the house. She has nothing more to do in her father’s home”, says 90-year-old Armine Petrosyan, who lives in Chartar, Artsakh, and often suffered from the rules when she was a young wife.

Local customs and the responsibilities of wives are changing with every generation.

Nowadays, only in remote villages (if there are any, now that the Internet has brought globalization even to the farthest corners of Artsakh) and in a few families can a woman be made to wash her father-in-law’s feet or visit her parents on a strict schedule.

Why women are buried a meter and a half deeper, and why men get the best piece of meat

What people throughout the world call gender inequality is considered tradition and custom in Artsakh, and people follow these traditions and customs as much as possible.

According to one of these customs, a man is the master of a woman (the husband is literally the wife’s boss).

“If the wife does not obey her husband, the whole village will point a finger at her and say, “I wish she had choked on her mother’s milk.” How dare a woman oppose her husband?” – says Tsiranik Gasparyan, 81-year-old resident of Zardakhach, known in the village as grandmother Senya.

Throughout her 63 years of marriage, Senya was convinced of one simple truth: a husband must not know where the soup ladle is in the house.

The wife must serve food and drinks to the guests invited by her husband, but she cannot sit with them at the same table.

However, a man must do the hard work.

“In a family where people love each other and live in peace, men do the hard housework. In general, a man is above everyone, and his word is the law for everyone,” says Senya.

She insists that no matter how long the distance from region to region, from village to village, the rules are the same for everyone; they call it “zakon,” the Russian word for law. In many cases, as women in the village of Drakhtik in the Hadrout region say, «պատճառը գիդասչըն», “we do not know why.”

The women definitely know one thing, “The best piece of meat in the pan should be given to the man, and the man should not open the lid of the pan”.

Moreover, the men of Drakhtik do not visit their mother-in-law’s house at all, says Venera Tonyan, a resident of the village.

Certain privileges or restrictions imposed on men and women do not always emphasize the superiority of a man. Sometimes this is due to superstition.

We asked Haykanush Badalyan from the village of Maghavuz about the restrictions imposed on men.

She put her thread and needle aside, thought for a while and then started to speak.

“They say that when women see men in the bakery, tonratun, they get confused. That is why men are not allowed to enter the tonratun. “

Having said this, Haykanush thought for a while and said nothing.

Social differences between men and women continue into the afterlife.

In Artsakh, according to tradition, women are buried half a meter deeper than men. This is because the man should always be above the woman, even in the grave. “There is a demon in a woman, that’s why we are buried deeper so that the forces of evil do not come out,” says Senya from Zarakhach, linking this tradition with Adam and Eve: Eve believed in evil more than Adam did.

Love is not measured by using each other’s first names

None of the nine children of 55-year old Ruzanna Aghabekyan had ever heard her address her husband by his name.

“She says: ada or ara, which means “hey you” in Armenian, or just talks to him without calling him by name. When speaking of him with friends or relatives she says “our husband, my husband”, and when talking to her children she usually says “your father”,” explains Ruzanna’s daughter, Sarine.

Sarine adds that of course neither she nor her siblings practice this tradition. Sometimes they even laugh at their mother’s behaviour.

“My husband’s name is Gagik and every time I call him by his short name, Gag, my mother looks at me strictly and says, ‘He is your husband, show some respect,’” Sarine says with a smile.

Surprisingly, even before the marriage, when they were still engaged, Ruzanna did not call her fiancé by his name.

“In my opinion, by using his first name, the wife makes it sound so cheap. And in an Armenian family, the wife and children should have deep respect for their husband and father,” says Ruzanna with conviction.

In the modern world, it is not easy to see the connection between name and respect. But in the Artsakh villages, this connection is still inextricable.

Ruzanna’s husband Samvel attended a Russian school, where he got the nickname Vasya. When her sister-in-law calls her husband Vasya, Ruzanna turns around and cracks up. To her, love is not measured by using first names.

As a child, Ruzanna spent several years in Shushi with her grandmother and learned a lot from her, including how to show respect for her husband. Her grandmother did not address her husband by name, and referred to him as “our father” in the presence of others. This was due to the deep respect she had for her husband.

And although the strict father of the family fondly calls her Ruzik or Ruzan, this does not change her view of respect.

Authors:

Susanna Avanesyan

Knar Babayan

Lusine Tevosyan

Sarine Hayriyan

Sketches by:

Alvard Grigoryan