The media of Artsakh use literary Armenian, but the dialect continues to be the language spoken by people in Artsakh

Print and online publications, the Public TV and Public Radio of Artsakh mainly write and broadcast in literary Armenian. In text format, journalists avoid using the dialect; they even translate quotes in the dialect into literary Armenian. However, audio and video do not work like that, so on TV, radio and in online multimedia formats, one can find direct speech and even whole programs in the dialect.

TV reporter Syuzanna Avanesyan is known in the villages of Artsakh as “the girl who speaks the dialect.” In 2009 she produced a program called “Pomegranate Seed” for Artsakh Public TV exclusively in the dialect. Syuzanna says that before launching the program, she studied the Law on Language and spoke to employees of the Language Inspectorate. Although the staff of the Inspectorate did not welcome her initiative, they said it would not be against the law.

“The program is about traditional song and dance, customs, cuisine and ethnic values. I thought it would be ridiculous to talk about these things to the village’s grandmothers in literary Armenian,” explains Avanesyan.

Overall, one can hear the dialect in just 4 out of 23 programs on Artsakh Public TV. Most of the time, hosts and reporters speak literary Armenian.

The Artsakh Times multimedia platform also has a program in the dialect, «Յո երթաս», “Where are you going.” The program is about the villages of Artsakh and the people who live there.

Tsovinar Barkhudaryan, the creator of the program, says that during her work as a journalist at Artsakh Public TV, she understood that trying to maintain a conversation in the literary language makes villagers’ speech sound artificial and insincere. During filming, she keeps the loudspeaker off because otherwise, the villagers become tense. During interviews, Tsovinar speaks to the villagers in the dialect. She says she wanted to do the voiceover in the dialect too but later decided to do it in literary Armenian.

“In online comments on my program, lots of people criticize my vocabulary. They say I shouldn’t be using Russian words, but I cannot help it because I speak to people in the Stepanakert dialect and it includes some Russian words. When talking to a neighbor, we do not, for example, use the literary Armenian word for ‘renovations’, we use the Russian word, remont. At the same time, I can say that as time goes by, our dialect uses more and more Armenian words and fewer Azerbaijani and Russian words,” says Tsovinar.

The dialect as a science

One of the main directions of Artsakh’s language policy is increasing the scope of study and description of the dialect, as prescribed by Artsakh’s Law on Language.

Over the years, scholars have collected samples of dialect speech and folklore, published texts written in the dialect, recorded songs, and produced studies on Artsakh’s dialect and folklore.

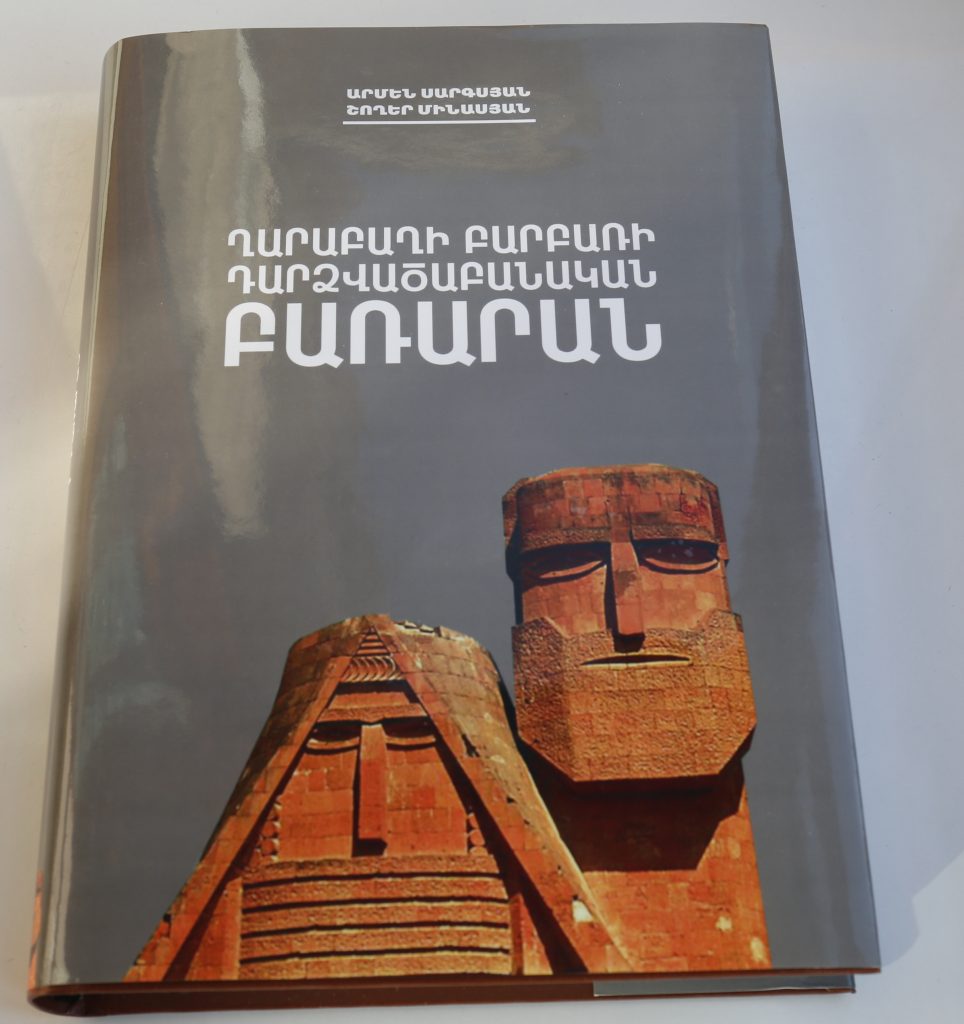

In 2013, linguist Armen Sargsyan published a dictionary of the Karabakh dialect, which included around 40.000 words. Four years later, in 2017, Armen Sargsyan together with his wife, Shogher Minasyan, who is a professor of the Armenian language at the Artsakh State University, published The Idioms of the Karabakh Dialect, containing descriptions and explanations of 15.000 idioms.

Armen Sargsyan has also authored The Folklore of Artsakh, a volume that includes 8000 folklore materials in 162 sub-dialects.

Recognition of the dialect is also highlighted in the educational sphere. The “Armenian language and literature” curriculum of philological departments at Stepanakert’s universities includes a 4-credit course of Artsakh dialects.

Today, Artsakh views its dialects as important cultural heritage. An organization called the Centre for Research of Artsakh’s Dialect and Ethnography, affiliated with the Ministry of Culture, Youth Affairs and Tourism, was established for the purpose of preserving, protecting and disseminating the dialects of Artsakh. The centre has two employees.

The social media speaks in the Artsakh dialect

There is a Facebook group managed by users from Artsakh named «Ինձ պետք ա էս հինչ ՊԵՆը!» (“Looking for something”), with more than 13.000 likes, resembling Babylon. People communicate here however they can, using whichever language they want. Generally, the Artsakh dialect is perceived to be the common language, often using the Cyrillic or Latin alphabet. To be fair, some posts use the Armenian alphabet.

One of the posts goes, «Ժողովուրդ հուվա գիդում դետսկի բալնիցին բժիշկները մինչև ժամը քանիսնն գործ անում??» (“People, who knows the working hours of doctors at the children’s hospital?”)

In social media, the language of chats between users from Artsakh is exclusively the dialect.

It is interesting that the Artsakh dialect has its own font, used for publications in the dialect. However, the font is not widely used on the internet.

An Armenian voice call app, Zangi, offers stickers in dialects, including in the Artsakh dialect. «Լյավը՞ս մատաղ ինիմ» (“Are you well, dear?”), «կլոխդ խարաբ ա՞» (“Do you know?”), «ծնգլհան ըրեր» (“It’s getting on my nerves”) and other similar expressions have become the favorites of Internet users.

“High art” in the people’s language

Besides being used in colloquial speech, in the last five years, the dialect has also become the visit card of many events, competitions, and festivals. Students of the Art School in the village of Togh, Hadrut region, have staged a play in their village dialect. Members of the theatrical troupe admit that performances in the dialect are received much more warmly by audiences.

“We feel more confident and calm when speaking our dialect onstage. Besides, one thing is to stage a performance in a well-known manner and language, another thing is to stage it anew and in the dialect,” says one of the actors, 17-year-old Arthur Sargsyan.

Youth from the town of Shushi who study at the Goris branch of the Yerevan Theatre and Cinema Institute prefer to perform in literary Armenian. According to them, there are many borrowed words in the dialect, depriving the Artsakh dialect of its initial purity.

“The dialect gives even the most wonderful drama a household feel,” says one of the students.

However, during classes, the students prefer to use the native dialect.

Today, the Artsakh dialect is also the language of literature and music.

Artem Valter, a native of Artsakh, became famous among Internet users with his song “Alo, alo” with lyrics in the Karabakh dialect.

Since its release on Youtube in 2011, the song has had about 300,000 views. We can say that this song made many people speak, or rather, sing in the Artsakh dialect regardless of their place of residence.

Afterwards, the singer released several more songs in the dialect, however, “Alo, Alo” remains the most popular.

When rapper Kolya, known under the nickname Fason, started rapping in the Artsakh dialect, Facebook was not very popular in Artsakh. His songs were distributed from phone to phone. A recently created band called Dibeta also performs only in the dialect; it is becoming popular on the Internet.

Documentary photographer and poet Anahit Hayrapetyan now lives in Germany. Originally, she is from the village of Khtsberd in the Hadrut region, and has recently begun to write poems in her native dialect.

Her most popular poem in the Artsakh dialect is called «Օզըմ ըմ» (“I want”)

| Օզըմ ըմ ես քեզ օզում ըմ | I want you, I want you |

| ծերքերդ | Your hands |

| պերանդ | Your mouth |

| մազերդ | Your hair |

| իմ ղաշանգ | My pretty |

| իմ սորուն | My lovely |

| իմ ջնավեր | My hefty |

| իմ նախշուտ | My handsome |

| ես քեզ օզում ըմ․․․ | I want you |

“I love the dialect, and we have always spoken it at home. It would be right to say that I think in the dialect. Things written in the dialect, with the exception of fairy-tales and the “Alo, Alo” song, are difficult to understand. I wanted to experiment a little to see what a poem in the dialect would look like – a simple poem, not too serious. In some of my poems, I managed to achieve that kind of simplicity. People loved the “I want” poem. Some took it as a joke, some got angry. For a while, I only wrote poems in the dialect,” says Anahit.

Political scientist Alexander Manasyan is well known in professional circles. In the Internet, he is known as the author of “The Tale of Artsakh Love” or “Արա պա ստի պեն կինի՞․․․” It was put on stage by drama students from Shushi.

A number of young writers, including Vachik Dadayan, Victoria Petrosyan and others, also write fiction in the Artsakh dialect.

Not only artists but also sectarians use the dialect’s publicity.

While the Armenian Apostolic Church, in accordance with the tradition, conducts its services and ceremonies in Classical Armenian (Grabar), Jehovah’s Witnesses active in Artsakh decided to be more resourceful and have started handing out leaflets in the Artsakh dialect. Previously, Jehovah’s Witnesses preached door to door in literary Armenian, but today they communicate in the dialect so as to make their message clear and understandable to everyone.

The Artsakh dialect as a brand

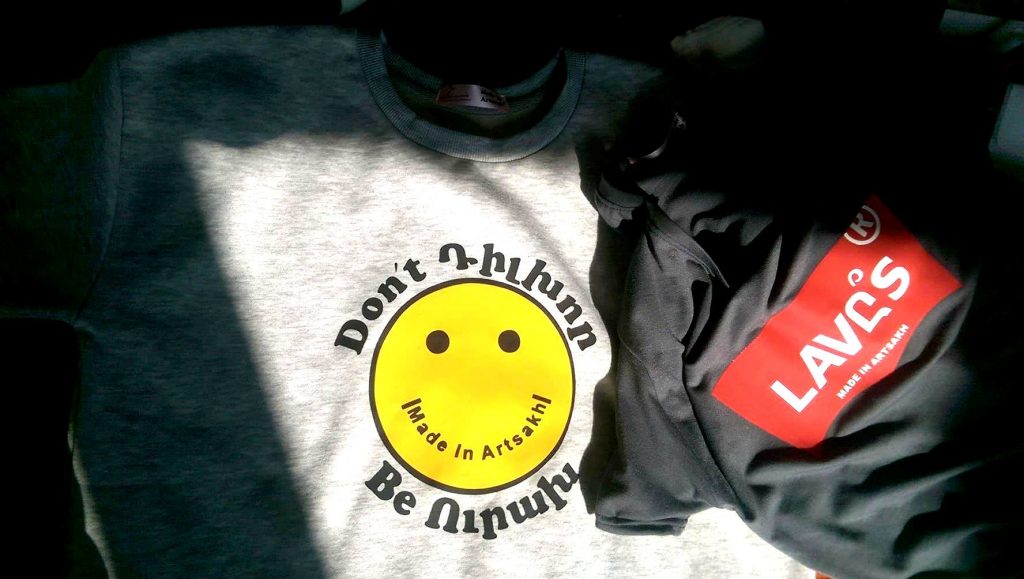

Azat Adamyan, 28-year-old entrepreneur from Stepanakert, has succeeded in making locally manufactured t-shirts trendy in Artsakh and beyond by means of creative inscriptions. «LEAVը՞S» (Levis), «Don’t դիլխոր, be ուրախ» (Don’t worry, be happy) and similar puns are created by mixing famous brand names, popular expressions and the Artsakh dialect.

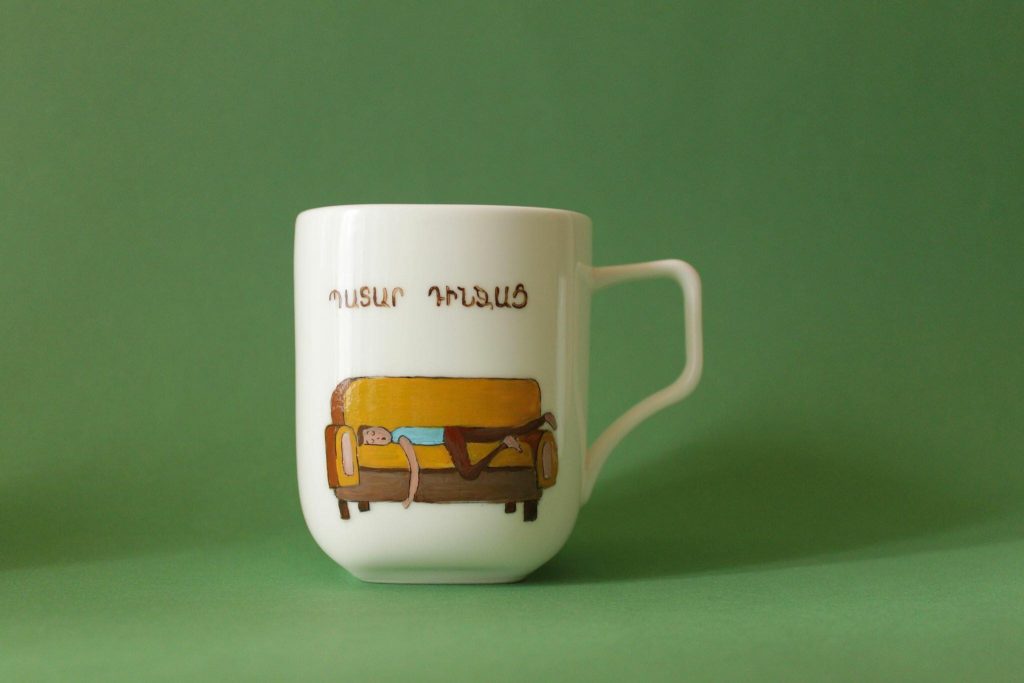

When designer Lilit Mailyan began making greeting cards and putting designs on cups a year ago, she could not resist using the dialect.

“Everything began with my first postcard, on which I wrote “եկ քեզ խտիմ” (Let me hug you). I think that the warmest things should be said in the dialect,” says Lilit Mailyan.

Appendix. The Nagorno-Karabakh Republic Law on Language Adopted on March 20, 1996. Excerpt from Article 1.

The official language of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic is literary Armenian. The Nagorno-Karabakh Republic promotes the unification of the Armenian spelling. The Nagorno-Karabakh Republic promotes the use of the Artsakh dialect, encourages its scientific study and publishing of ethnographic collections in this dialect.

Authors:

Syuzanna Avanesyan

Narine Aghalyan

Knar Babayan

Sarine Hayriryan

Alyona Melqumyan

Mariam Sargsyan

Marut Vanyan